In Ancient Greece the three Moirai were goddesses who handled the thread of our lives.

The first of these “Fates,” as they’re sometimes called, was a goddess named Clotho, the spinner. She would arch over her spindle and weave human life, spinning a thread from its moments. Her sister Lachesis, the allotter, took stock of our threads with her measuring rod, deciding when our story was woven to completion. The third sister, Atropos, would then decide the final act of life, and snip our thread with her shears, bringing the story to completion. Her name means “inevitable” or “unturning”; the cessation of spinning, the story we can’t escape.

This myth is a story about stories; an answer to questions that were hard to define and even harder to prove. Why are we here? Who is calling the shots? It’s a story about the weaving of our stories, both personally and collectively—a means of understanding who we are as people.

Humans have told stories to make sense of the world since the beginning of time. The earliest stories are in the Lascaux Caves of Southern France. Primal narrative of the art of survival, the ritual of the hunt, painted on the walls in 13,000 B.C. Aesop crafted his fables of ethics and virtues, tales of what it means to be human in 500 B.C.; tales that we still tell to this day.

Our ancestors took sounds and created speech, symbols and created language. Alongside opposable thumbs and a sophisticated prefrontal cortex, stories are the trademark of being human. We’re distinctly wired for narrative, both that we collect and that we create.

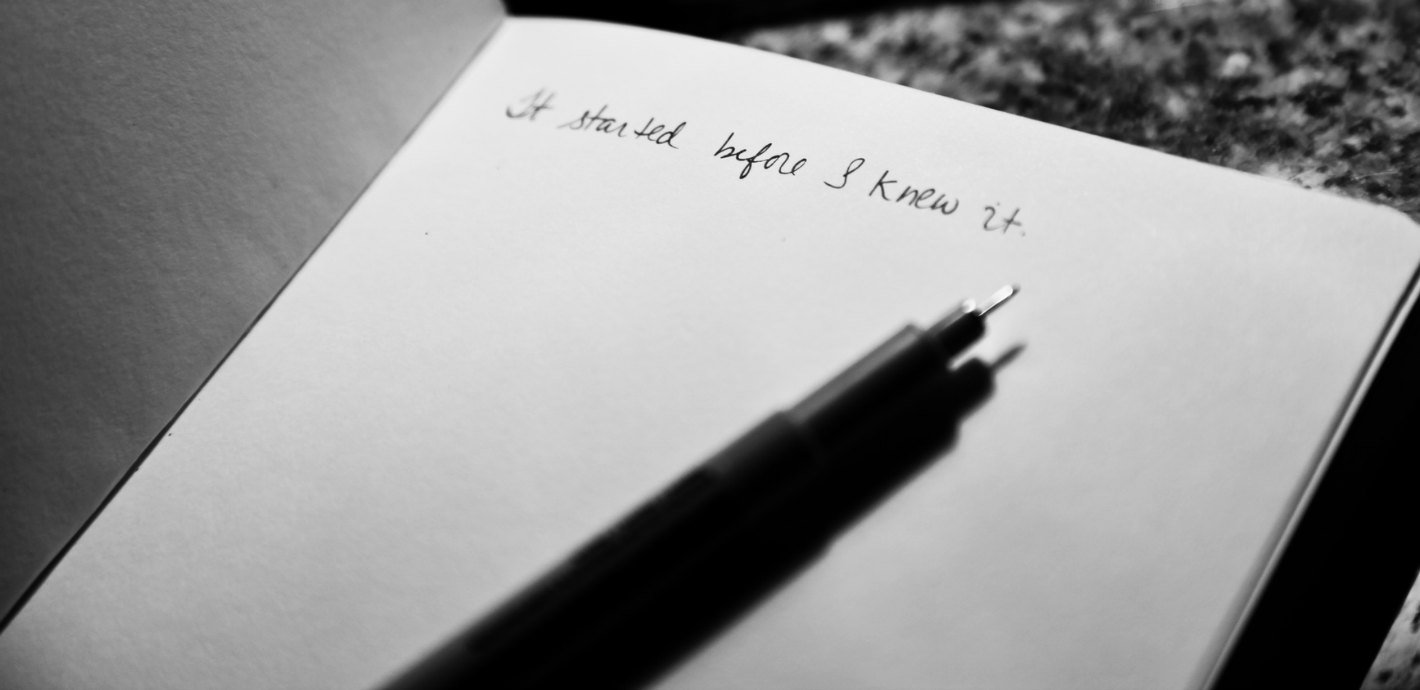

If you’ve ever sat down to meditate, it’s easy to see the narratives that we spin, on and off the cushion. We have an unobstructed view of our thoughts: One moment we’re in the future, planning our dinner, our presentation, how to allay the outcomes we fear, and create the ones we desire. The next moment we’re in the past; analyzing a conversation we had on Tuesday, what we could have said differently, the tone of our partner’s response. We sift through our stories to collect meaning and information, weaving our threads from the contents we find, building our perspective on ourselves and the world around us.

The novelist Virginia Woolf once described our sense of self “like a butterfly’s wing…clamped together with bolts of iron.” And indeed, our mind flitters like a tiny time traveler, riding the length of our stories.

Cognitive science and psychology agree, with the study of narrative identity pointing to the flexibility of self. It’s the measured assertion that we don’t just tell stories, we are our stories; bound together by our beliefs and experiences. This makes our stories, and the qualities of our stories important to who we are. The question then becomes, what are the stories we’re telling ourselves if they’re the script of who we become?

The ancient Greeks gave our life’s story to the Fates, but may have misunderstood the place of the narrator. The power of any story is that it’s infused with a point of view, and told through the narrator’s interpretation. In other words, we own our stories; no one else can tell them for us.

There’s an old Chinese fable of a farmer and his neighbors. One day the farmer’s only horse escaped from its corral and ran away. The neighbors came when they heard the news and stood around shaking their heads. “Oh what bad luck!” they lamented, but the farmer simply shrugged. “Perhaps.”

About a week later, the horse returned, bringing a whole herd of wild horses with him. As the farmer and his son corralled their new stock of horses, the neighbors stood by and rejoiced. “Oh what good luck!” they declared, and the farmer replied, “Perhaps.” The story continues like this with an unfolding of good luck and bad, but to the farmer, a matter of perspective.

We can’t predict the cards that we’re dealt, but we have agency over how we interpret them. A tragedy, a blessing, a story of redemption, forgiveness, revenge: Regardless, we are the narrator.

Some of our narratives are so entrenched that the story begins to tell us. That’s when story becomes dangerous; when we’ve lost ownership of our interpretation. We begin to view things as “just the way it is”, which breeds cynicism, passivity, and doubt.

Imagine being a woman in 1848, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and 100 colleagues gathered in upstate New York to reevaluate a popular story line. The question was “What does it mean to be a woman?” and they didn’t believe in the assumed answer. It was a story that was so deeply embedded that we as a society mistook the status quo for truth. There’s a popular adage in public relations; “If you don’t like the conversation, change it”. I’ve never worked in PR, but I’ve always loved this saying. It’s a permission slip of personal agency, and reminds us that our story is in each of our hands.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton decided it was time for a new narrative, an updated story that would answer the question of who we are, and 19 years later Wyoming was the first state to grant women the right to vote, with the rest of the nation following suit, tipping the scales of women’s equality.

Our cultural heroes and those who have changed our collective conversation possess diligence and faith, but most of all, imagination; they saw a story that needed to be told and told it.

On a personal level, all change begins by recognizing that we are the narrators of our stories. If we believe that we don’t deserve it, or that others are generous, or that the grapes are sour anyways, then we’ll act in ways that confirm our suspicions. The psychological term for this is confirmation bias; but we can call it the power of personal narrative. We’re always seeking out information that colludes with our story, and behaving in ways that confirm it.

Stories run deep, often the length of our lives, and are not always easy to change. Sometimes shifting our narrative requires splicing, healing, or the force of Atropos’ proverbial shears. However as long as we recognize that we own our narrative, the stories we collect and the stories we create are under jurisdiction of our point of view; they can be rewound, reinterpreted, reviewed, and reimagined.

Moment by moment we choose the ones that we tell.

Comments (0)