There are many reasons to meditate, and lots of reasons why people don’t, or don’t want to. My friend Adam Grant wrote a hilariously grumpy screed in the New York Times late last year about how he’s exhausted with everyone telling him to meditate. You could certainly say meditation is having a moment, but then again, meditation has been having a moment for a while now.

The myriad benefits of meditation practice include lower blood pressure, less anxiety, and a greater ability to focus. A growing body of research supports these and other positive health effects.

I have been meditating since I was three years old, so it is sometimes hard for me to put my finger on what meditation does. I can’t tell you that I am a stress-free, vice-free yogini. While those 36 years of practice—give or take—have given me a lot of quiet, it hasn’t made me quiet. And I should say that I dropped my practice for years, choosing instead a nice glass (or three) of Chablis, or the ease of an anti-anxiety medication, or the rigor of an hour-long trail run. Or countless episodes of Law & Order. All of those things do something for me, which is tune out, for a little while, the chatter in my head.

Meditation can do that sometimes, but often it doesn’t. Instead, it forces you to reckon with the chatter and cleave it away from your sense of self. The most fundamental thing I’ve learned from a lifetime meditation practice is that my thoughts do not define who I am. That’s a neat concept and I feel forever lucky that it is a position I was able to understand from an early age. But actually living that idea—not getting dragged high and low by the ticker tape of thinking—is as far as I can tell an unreachable goal that is totally worth having.

For me, meditation is the best thing I can do to steady my emotional state, to feel rested, and to remind me of that silent state that I think of as myself. It is a part of me that, these days, feels especially vulnerable in the face of the onslaught of connectivity and the responsibility that comes with that.

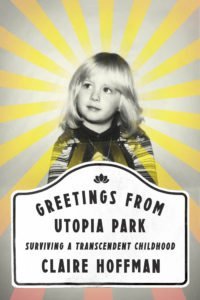

Part of what my new book, Greetings from Utopia Park: Surviving a Transcendent Childhood, deals with is this conundrum: It’s hard to meditate. And people who are super into meditating have, for me, historically gotten kind of crazy. So I have mixed feelings about meditation—meditation became a religion for me as a kid and when I left that world behind, I left the regular practice of meditation.

When I was five years old we moved to Fairfield, Iowa, from the Upper West Side of Manhattan. We were part of a group of thousands of people who came to Iowa in those years, beckoned by the call of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the “giggling guru” who developed the Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique and was made famous by his relationship to the Beatles. Initially, the movement he started was all about the daily practice of meditation. And it caught on like wild fire, with millions of people learning it in the 60s and 70s. But by the 80s the TM movement had become focused on the grander goals of our guru. Of these, yogic flying to create world peace was the biggest. But there was also an expanding knowledge from Maharishi—what to eat, when to sleep, how to dress, gemstones, astrological charts, and an entire style of architecture and home building.

By the time I was 17, it was all just too much for me. Meditation wasn’t really working for me, and as far as I could tell a lot of the adults around me, who spent three to four hours a day meditating, seemed super stressed out. Who wouldn’t be with all these guidelines and restrictions on living?

But now, as an adult, I have come back to meditation. I need it now in a way I never did as a kid. The constant buzz of the cell phone, the persistent whine of my children, the never-ending to-do list in my head, the anxiety of work, and parenthood, and wifedom. I’ll admit it; I find modern adult life exhausting and anxiety-inducing. But don’t get me wrong—I’m not a “meditation is the answer” person. I agree with Adam Grant. A nice long jog can give you a similar clear-headed feeling. Plus, it burns calories. And sometimes, it is easier—and perhaps more joyful—to pour yourself a glass of wine and eat with friends than remove yourself to meditate alone. And when I’m losing my shit, I simply can’t go sit in my room alone with my thoughts. Sometimes, drugs are the answer. For me.

“Well, that’s boring,” you might be thinking, “That’s like a non-answer.” And I agree. That’s part of why I wrote my book. I think what really freaks people out and makes them anxious is the idea that there is an answer. Or a perfect way to be. There’s a constant yearning and strain to leave behind who they are and become someone else. And that’s where unhappiness comes from. That’s why I find the idea of having a guru unattractive—the idea of seeing someone else as perfect in opposition to your flawed self.

So I come back to meditation but without any idea of what it should be. I don’t think about it, I just do it without an expectation of some amazing experience or an elevated level of consciousness. I meditate because I feel a little better afterward. And I like that.

Claire Hoffman is the author of Greetings from Utopia Park: Surviving a Transcendent Childhood, a memoir about her experience as a child in the heartland, growing up in an increasingly isolated meditation community in the 1980s and ‘90s. Visit her website to learn more about the book, on sale June 7.

Claire Hoffman is the author of Greetings from Utopia Park: Surviving a Transcendent Childhood, a memoir about her experience as a child in the heartland, growing up in an increasingly isolated meditation community in the 1980s and ‘90s. Visit her website to learn more about the book, on sale June 7.

Comments (1)