Winter across the vast expanse of the plains states is bare; it is not bleak. There’s too much necessary rejuvenation occurring in those fallow fields of snow and corn-stalk stubble to call it bleak, but it is spare and severe. It was against that backdrop that ten years ago, while driving across Ohio, I saw something wonderful and astonishing: barn art. I saw it on I-71 north of Columbus, Ohio, and then again on I-70 east of Dayton. It was Ohio-centric art in celebration of its bicentennial in 2003, and it was amazing.

The role of art in our society and its impact on us both individually and collectively has long been deliberated. Auden famously said that “Art accomplishes nothing,” while, at the other extreme, Abraham Lincoln, upon meeting Harriet Beecher Stowe, allegedly said, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.” Of course, Uncle Tom’s Cabin did not make the Civil War: one half of our country allowing one race of people to own another race, and Lincoln’s refusal to let that continue, is what made that war. But it is fair to wonder and speculate on art’s effect in our world. My Dante professor in graduate school once told us of some famous London conductor who, during the German blitz of his city in World War II, stuck his phonograph in the window and played Beethoven’s Ninth while the planes bombed and droned. The music did nothing to deter the planes and bombs, but it must have fortified that conductor in some essential way. And also perhaps his neighbors, who must have heard the music.

It’s certainly fair to discuss the societal impact of public art because societal impact is the reason for its existence. Barn art is public art, massive depictions painted on a massive canvas for anyone who might happen to drive by, which is what I did in Ohio about ten years ago. Prior to then, I had not seen any barn art since I was a little kid in rural Illinois. Janice Meister was a classmate of mine, and when we were in first grade, her mother (whose name I cannot recall), painted one of their barns which stood near their house two miles outside of town about fifty yards off of the road. It was remarkable what she painted—a black silhouette of her husband in his tractor set in relief against a sunset background, green corn, golden sky. It was huge. I have no idea how she did it.

The barn artist in Ohio responsible for the bicentennial pictures I first saw ten years ago is named Scott Hagan. He’s thirty-nine years old, lives in Jerusalem, Ohio, is married with two kids, and came by his passion the way many of us do: instinctively.

Related: Balancing the Voices of Intuition and Logic

“I was just looking for a new challenge,” he said. By that, he means he wanted to try his hand at a larger canvas. Largely self-taught, Scott attributes his artistic ability to his grandmother and especially his mother, and throughout grade school and high school he painted just about anything he could—paper, mailboxes, birdhouses, cars. But as he said, he wanted a new challenge, “and at that point the biggest canvas I could find was Dad’s barn, so I asked if I could paint something on it.” Scott wanted to paint a Tasmanian devil, but his dad didn’t want that, so they settled on an Ohio State Buckeye with Brutus (the Ohio State football mascot for those not in the know.)

Enter serendipity.

Of course Scott’s grandfather was impressed with what Scott had done—he was his grandfather, after all (not to mention probably a Buckeye’s fan). So he took a picture of the work to the local newspaper, The Barnesville Enterprise, where the editor was so impressed that he gave it front page coverage. The story was in circulation just when a state official responsible for helping to plan the upcoming state bi-centennial was in town. Originally, the talk in Columbus had been to put up a billboard in every county honoring the bicentennial, but this official had something else in mind, something more lasting that harked back to her own childhood many years before.

Throughout much of the 20th century, barn art was used as advertising—companies hired artists to paint barns along the sides of roads in order to advertise their products, much like this John Deere painting Scott painted for one client.

It all came to a halt in 1965 with the passage of the Highway Beautification Act, but by then thousands of barns across the country were painted with an advertisement. The king of barn painting was a man named Harley Warrick, and he estimated to have painted over 20,000 barns himself. That official from Columbus remembered those barns from her youth, so after being in eastern Ohio at the right time to see the newspaper story on Scott’s Buckeye barn, she contacted Scott to offer him the job of painting a barn to commemorate the upcoming bicentennial in every county in the state. 88 counties. 3 years to do it. He took the job. But the serendipity doesn’t stop there.

With so many barns and so little time, Scott knew he had to devise a better system. “For that first barn, I just climbed on a ladder, and I painted with one hand and had the design on a piece of paper in my other. I’d paint a section then get down and move the ladder around and paint another. It wasn’t very efficient, but I didn’t know what else to do.” It was at this point that Scott’s father mentioned that someone who used to be a barn painter lived not too far away: Harley Warrick. Scott gave him a call and arranged to meet the master.

Harley showed Scott how to use a block and tackle system, a rope and pulley, to move a platform up and down on which he could stand to paint, and Harley even gifted Scott the stage upon which he stood for many of his years. Harley also shared with Scott a common adage that isn’t common the first time you hear it: “If you can find something you like to do,” Harley told Scott, “and you can find someone to pay you to do it, then you’ve made yourself what you want to be.”

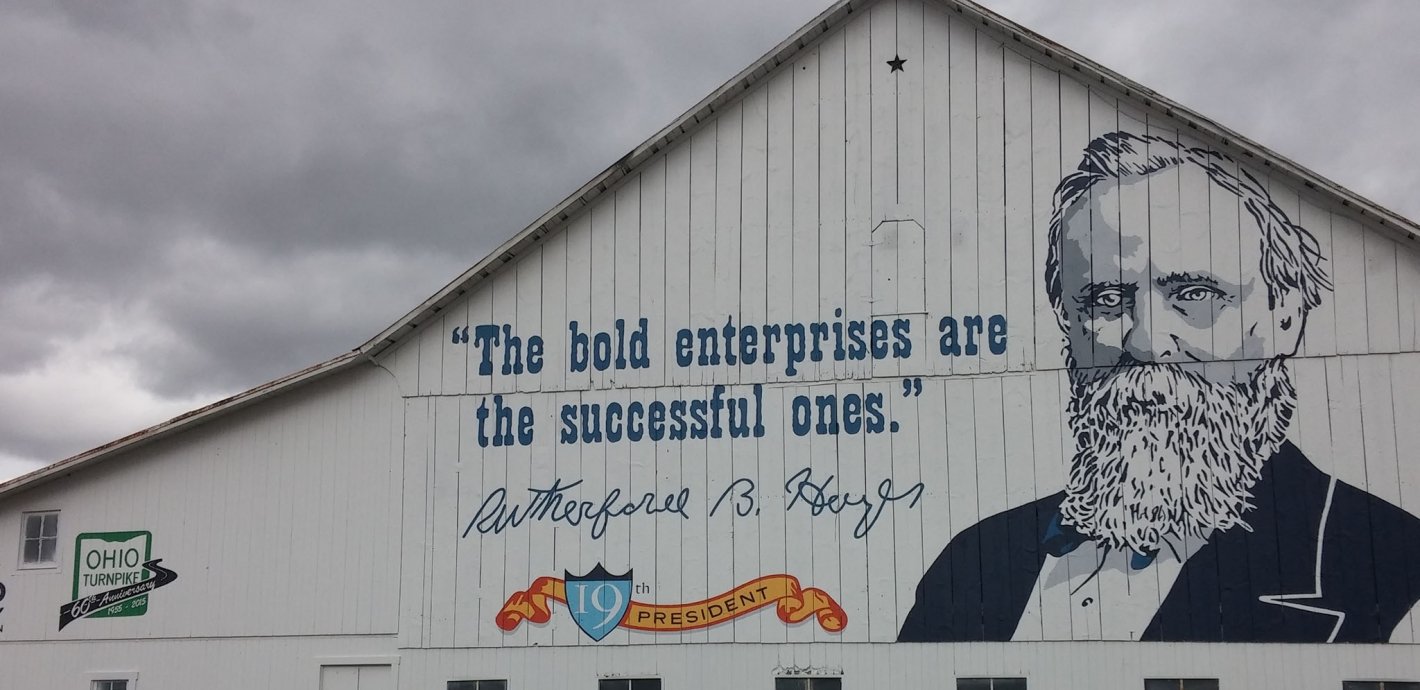

Scott has made himself what he wanted to be. Since the bicentennial job, he has had steady work painting all kinds of barns around the country—his work can now be seen in eighteen states, and his goal is to paint a barn in all fifty states. His work covers a wide array. Sometimes it’s an advertisement for a company or cause, sometimes it’s an idiosyncratic request, sometimes it’s another historical commission, such as when he painted a barn dedicated to President Rutherford B. Hayes’ in Hayes’ home county in northwestern Ohio, and sometimes it’s another commission for a major project, such as when Monroe County, Ohio, hired him to paint quilts on twenty of its barns.

I asked Scott if what he did was a calling, language he’s not uncomfortable with as a devout Christian. “Maybe that’s the word,” he said. “I believe it’s wholeheartedly what I’m supposed to do, paint these barns.” At one time early in his career, he was under pressure to take a job at a nearby plant as it seemed to offer more security for himself and his family. It was offered, “but I felt so strong about what I wanted to do that I turned it down,” he said. “A year later that company folded, and I’m still working.”

Related: How to Tap the Power of Intention This Year

Part of what makes an artist, of course, is his or her vision, an ability to see what most of us cannot see, and where most of us see a barn, many of them beautiful structures in and of themselves, Scott sees something else—a canvas. Potential and possibility. “I have driven around and seen so many barns that I really hope I get to paint something on someday.”

Not all barns are alike. They differ in material—some are wood, some metal, some with batten strips, and that material sometimes helps to determine the art. “Metal barns all have ribs about every five inches, long vertical bumps. You can’t pull the paint as easily as you can across a flat, wooden surface. It’s just a lot harder to do a diagonal line across an uneven surface, so for metal barns, when I can, I avoid designs with diagonal lines.” Barns also differ in age, some older, some newer, some vintage or antique. In their difference is their aesthetic, and Scott tries to match a picture to that aesthetic and will subtly work to guide customers to meet his vision. One customer in Illinois had an old, weathered, wooden barn, and Scott convinced her to go with a Coca-Cola ad from before World War II. He even scuffed and burnished the final product to make it look older than it actually was.

Then there’s the ritual of the actual job, which begins with the drive to the site. “I meditate on that drive about the work ahead. By then, I’ve seen pictures of the barn, and I’ve settled on the image the client wants painted, but you can’t get a real sense of the job until you see the actual barn.” Which is why when he arrives at the worksite, after he’s officially met the client and before he begins painting, he stands back and stares at the barn for quite a while, like any painter before his empty canvas. Then comes the painting, the quiet, deliberative process that Steinbeck once called, “The indescribable joy of creation.”

“It feels special when I’m out painting,” Scott said.

His favorite job was one he had last fall for a barn so remote that the only people who were ever going to see the work was the man who commissioned it and his family. “That guy was passionate to have his barn painted, for himself, and I was passionate to be there painting it. It was quiet the whole time. All I heard was the sound of nature. I relish that quiet. It’s meditative. The more quiet and meditative a job is, the more I come home a better person. I’m blessed in so many ways, and I’m so thankful for all of it.”

I asked Scott what impact he hoped his art was having on the public. “I haven’t really thought about it,” he said, which was such a refreshingly humble, unself-conscious response to hear an artist make. Then I asked what impact it was having. “People tell me on Facebook to keep up the good work because they like seeing it. They say they appreciate me beautifying America in this way.” Clearly, Scott was uncomfortable talking about himself, but he became much more effusive when I asked the impact public art had on him.

“There’s some public art in Bucyrus, Ohio, that you really have to take note of,” he said. He was referring to massive murals painted on buildings by the artist Eric Grohe. “I stand in front of those murals, and I wonder about the artist who has the talent and takes the time to paint like that. The work looks 3-D, and on that kind of scale—for me, that’s beauty.” He continued, “In Portsmouth, Ohio, there’s a mile-long flood wall with murals all over it. The stuff is picturesque. It’s a bunch of individual pieces of art about 40 by 20 feet. It’s beautiful. When I just stand there and look at that stuff, I take the moment and forget about everything else in the world.”

I have seen Scott’s work in person only by happenstance, which is the best way to come upon something wonderful, and only in winter, which for me is the best time to see that work. Growing up, I saw the barn Janice Meister’s mom painted in every season; in autumn and spring it was part of a nature’s busy mosaic, and in summer, once the corn got high, you could hardly see any of it from the road. But in winter it was a different story. Against the backdrop of the plains in winter, Scott’s art was captivating, ecstatic, warm and reassuring. It was filled with humanity.

Related: A Poem for Hope in Overcoming Depression

In his prose poem, “Prairie Farmstead,” the Midwestern poet Tom Hennen writes about the imminence of one night in winter: “The farmhouse lights have come on and throw warm yellow into the dark. Those still outside with chores they must finish know there is something they cannot name, a chill they feel not from the frost. Then the animals watch the humans closely. When the first call of the owl floats out of the cottonwoods the night has begun. The sentry is in place until morning light. All is well.”

All is well. That’s what seeing Scott’s art on those December drives made me feel. Will all be well? For some, certainly, but not for all and not all of the time for any of us. It never is, and it has always been thus. And yet, on a winter evening when the sun began to fade and I saw one of Scott’s paintings, it became easy, just for a moment, to believe that all was well for all. Knowing better was irrelevant. Scott’s passion brought me that moment of grace, which may be the most any work of art, public or private, can truly deliver, but surely that is enough. Moments of grace are precious and dear, and the more each of us have, the better each of us, and our world, must certainly become.

Comments (0)