I began practicing yoga in my late twenties, ostensibly to find physical relief from many years of badly aligned activities. I was intuitively drawn to yoga rather than some other therapeutic discipline because it seemed ancient, timeless, and unchanging, and I thought those qualities may hold the answers to all of my existential questions about life. Even the word “yoga” had some kind of mysterious power.

These things I now know to be true, but I have come to realize that it is the ongoing physical practice of yoga that is necessary for the deeper insights of yoga to occur.

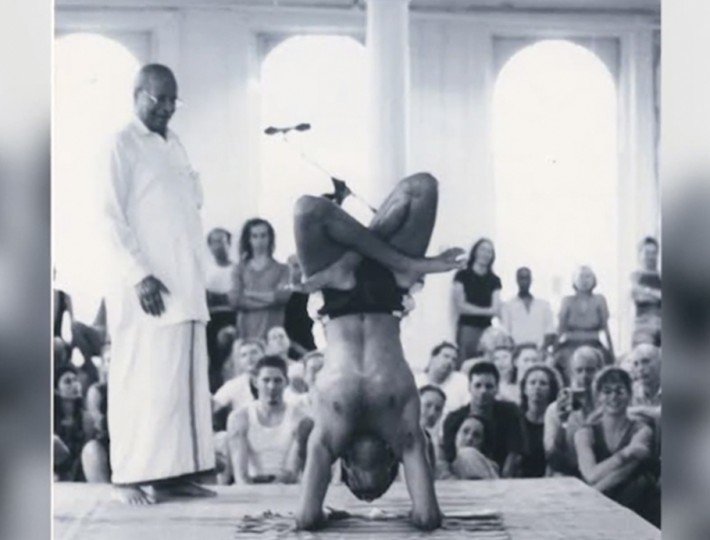

The Lineage of Aṣṭāṅga Yoga

In the early 1990s, when suffering from sporadic severe back and neck pain, I began practicing Aṣṭāṅga yoga in the Mysore class format, sweating my way through the primary series every morning. Although working in the physical realm, I became aware that I was also dealing with some subtle and more internal aspects of myself.

Yoga practice was like bringing a small, dim candle into an attic and beginning to find all sorts of unnecessary and potentially deleterious material that needed to be dealt with. Cleaning out the attic was (and still is) a slow and not always pretty process, but it is why I practice and what continues to sustain my yogic sādhana.

It was extremely helpful for me, especially in the early years of practice, to be surrounded by a community of teachers and students who were all dedicated to the same practice method. From my first trip 20 years ago to practice with Guruji and Sharathji at the Aṣṭāṅga Yoga Research Institute in Mysore to the many subsequent times practicing with them at KPJAYI, I always experienced a deepening of this transformational process. I recognize their profound influence on all of us in the room and have been humbled by the Aṣṭāṅga paramparā that has flourished under their guidance.

The Monier Williams Sanskrit-English dictionary defines paramparā to mean “an uninterrupted row or series, order, succession, continuation, mediation. Lineage or progeny. By tradition.” The broader meaning of “paramparā” implies far more than this simple definition. Paramparā is very important in many of the spiritual disciplines in India, and many individuals chant a daily mantra that lists their spiritual lineage, often reaching back a thousand years or more.

What has become clear to me from years spent studying yoga (and the related disciplines of Vedic chanting and Vedic philosophy) is that the profound nature of these kinds of experiential teachings does not come through books or videos. Those are only a support for learning. The teachings come full force when imparted directly from teacher to student within close physical proximity. Even the word upaniṣat (used as a moniker for philosophical texts in the vedas) implies receiving teaching when “sitting near” the teacher.

Transmission of knowledge is strongest when successive teachers within an unbroken lineage have been completely immersed in, and surrounded by, their discipline, especially when cradled in a culture and environment that supports their understanding and internalization of the subject. Such a teacher becomes drenched in experiential knowledge and cannot help showering his students with the authentic teachings of yoga.

Related: What It Means to Celebrate Guru Pūrṇimā

In the lineage of Aṣṭāṅga yoga, Ramamohan Brahmachari, Krishnamacharya, Pattabhi Jois, and now Sharathji are a line of teachers who have been fully immersed in yogic sādhana in this way. We should not quibble that there may have been changes to the exact methodology that they have used, since the method will always be adapted to suit the times. In yoga, maintaining a static and rigid methodology is not the purpose or result of true paramparā. Rather, it is how to support the continuation of the experiential understanding of the “state of yoga,” that eternal and unchanging condition, which is most important.

The Energy Within All of Us

In February I made yet another pilgrimage to practice at KPJAYI, and this time Sharathji asked me to come not just to study with him but to lead the primary led classes at KPJAYI while he was away in Rishikesh for a few days attending a conference.

Calling the vinyāsas of the primary series to a class of 350 of Sharathji’s dedicated students was extraordinary, but what struck me most while leading these classes was how strongly I felt the energy of both my teachers, Sharathji and Guruji, coming through the students. I did not feel as though I was teaching the classes but that I was simply holding the space for Sharathji. I was following the energy of my teachers that was already present within the students, allowing the practice to emerge and only assisting the process.

Having taken hundreds of led classes with them over the last 20 years, I also felt Sharathji and Guruji’s energy from within myself guiding me as I called the class. This was evidence of the profundity of the Aṣṭāṅga paramparā that we are all part of as students in this lineage. It reminded me that, as students, we are also an indispensable support of the Aṣṭāṅga paramparā and have a responsibility to devote ourselves wholeheartedly to understanding the practice so that we can support the journeys of those students who are just beginning.

Inspired by the Puruṣa Suktam, Viśiṣṭa Advaita philosophy teaches that we are all part of the body of the Paramātman. We are a part of the whole, and each of us fulfills a role. At the same time, the Paramātman also resides within our own ātman (soul) as the antaryāmin (inner controller), guiding and directing each one of us. As part of the Aṣṭāṅga paramparā, we all have our role, and through the teachings and by consistent practice over a long time, we are able to gradually remove the dirt that clouds our perception, leading us to connect inwardly to this antaryāmin, the source of pure sattva or light.

Comments (0)