In 2008, Michelle Golberg had just finished a journalistic investigation of women’s rights around the world for her book, The Means of Reproduction: Sex, Power, and the Future of the World, and was wrapping up her intense coverage of the presidential election. “At the time I thought (wrongly) that there might be some sort of respite from the culture wars…and that it was a time I could take a break from politics and turn to something else,” she says. And so she turned to Indra Devi, a Latvian-born visionary who was one of the very first people to bring yoga to the West in the mid 1900s. Goldberg began with a personal inquiry into the authenticity of her personal practice and yoga more broadly, but ended up discovering what she calls in her introduction, “a secret sideways history of the 20th century.” Her groundbreaking text dispels many of the misconceptions spandex-clad Western yogis have about the origins of the yoga practice, while telling a powerful story of a woman who saw her “freedom as absolutely paramount, at a time when women’s freedom didn’t have a lot of social support.”

Why did you choose Indra Devi as a subject for your new book?

This was a book that I really wanted to read before I wanted to write it. I first discovered Indra Devi when I was looking for a secular cultural history of yoga, a book that would tell me where these traditions really come from and how much of what I was hearing in my yoga classes I could actually take seriously, and how much of it was myth or magical thinking.

I was just procrastinating at work and Googling and going down the Internet rabbit hole, and I came across Devi’s New York Times obituary. I thought, well, this is an incredible story. I’ll just go buy a book about her. I went to Amazon and found out there wasn’t one, and for years would tell my agent, “You have to get someone to write a book about Indra Devi. It’s not the kind of thing that I do. I’m a political writer, but someone has to do it!”

Then after finishing my book on women’s rights, I took a pause to turn to something else. For me, this story and research was a refuge after having been immersed in this milieu of rage and recrimination for years and years. I think I thought that it was going to be a relatively short project. I thought I could do it in a year or two and ended up taking five.

In your book you focus much attention on the fallacious notion that there may have been some “pure” Indian philosophy that Westerners adapted over time or that we somehow appropriated and muddled “true yoga.” Can you explain why uncovering the truth about the interplay between different cultures has been an important element of your research?

Initially part of what drew me to the subject was wanting to know where this discipline, where this series of postures and exercises that I was practicing several times a week for 90 minutes on a rubber mat, where did that really come from?

I spent enough time in India to know that yoga as we practice it in Brooklyn or San Francisco is relatively hard to find on the subcontinent, and particularly outside of forest enclaves. I had heard people who were serious asana practitioners explain this away by saying that Indians have just lost touch with their heritage. But I think if you’ve been in India, there are not very many countries where people are more in touch with their heritage, and where the past and present coexist so dynamically.

There was a tendency among Westerners to see Eastern countries as these static repositories of unchanging wisdom, when in fact they are as dynamic and innovative as a country in the West. They are very much participating in modernity.

I had a sense that there was an untold story there. Then when I started looking at the academic literature, it became really clear to me that there was a huge gap between the academic understanding of where asana practice and particularly Vinyasa practice and Sun Salutations came from, and the popular understanding of where it came from. Then as soon as I grasped Krishnamacharya’s role in creating yoga as we know it, it became clear that it was because he was such a pivotal figure in Indra Devi’s life, it became clear to me that it was a huge part of this narrative.

What was one fact or experience from Indra Devi’s life journey that you uncovered or learned of that was particularly striking and fun for you or really kept you up at night?

Can I give you two?

Yes, please.

When you write a biography you have this weird relationship with your subject because on the one hand, you have to adore them to spend all this time with them. On the other hand, anyone whose life is subjected to the scrutiny that you have to subject it to, you can’t emerge from that unblemished.

The thing that was most troubling about her I thought was that she treated her second husband really terribly. He had a stroke and they were living in California and she brought him to India, because she wanted to be there, but then she didn’t want to be by his side and so left him in the care of attendants while she went and traveled around the world. He hated India and died lonely, away from everyone that he loved. She knew and admitted that she didn’t treat him well, but justified it in terms of the yogic imperative for detachment. She always said that she combined love and detachment.

To me, beyond just it being really emotionally disturbing for this one very sweet man, I think that there is something there. I think that it got at the larger way in which Eastern, whether Hindu or Buddhist beliefs, when wrenched out of context can just become alibis for selfishness, which I think you see a lot in the New Age world. That’s certainly been a subject of a lot of critique of the American New Age movement.

The part of the book that I found so much fun to write about was her time in Panama. Partly because one of the things that attracted me to her is the fact that she keeps cropping up at every pivotal historical moment of the 20th century. Then she shows up in Latin American guerilla forces in the 80s. It’s like, “Wow, even here?”

The story is so crazy. She becomes the spiritual advisor to Noriega’s second in command, Colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera, and inspires him to really think that he would use prana [the yogic term for life force] to defeat Noriega, and ultimately she did set off a series of events that led to an uprising against Noriega and then to the American invasion. It was just astonishing, I thought.

You’ve mentioned the way in which yoga was not only an important practice for you throughout the writing of this book, but also a main impetus in embarking on this research. How has your relationship to your yoga practice changed over the course of this endeavor?

Well my yoga practice has changed for reasons that have more to do with passage of time than with the book. I had no children, nor any plans to have children when I started the book; now I have two. So, whereas I was practicing four to five days a week then, now I’m lucky to be able to practice two or three days a week.

Whatever anxiety I had about yoga’s authenticity or what I was really doing on the mat and whether my time would be better spent doing Pilates, a lot of that has been resolved in the course of writing this book because it made me realize that there is no reason to worry that we’re corrupting some unbroken, authentic traditions. There is no authentic tradition to corrupt. It’s been a process of innovation and adaptation, particularly since the advent of modern Hatha yoga.

It makes me feel less anxious about, “Well, is what we’re doing ‘real’?” I go to a studio called Prema in Brooklyn, New York, and they’ve recently created a “Prema sequence”—a sequence that a bunch of different teachers at the studio teach. A purist might say, “Well, where do they get off creating their own yoga system?” Having written this book, I feel like they have as much right and they are obviously respectful and kind of learned teachers. They have as much right to innovate as anyone else; it’s what people have been doing all along.

Although I think there is something maybe a little bit disillusioning, when yoga is first demystified for you, and when you realize that Patanjali never wrote anything about Triangle Pose. Ultimately, I think that once you come to terms with that, there is something liberating.

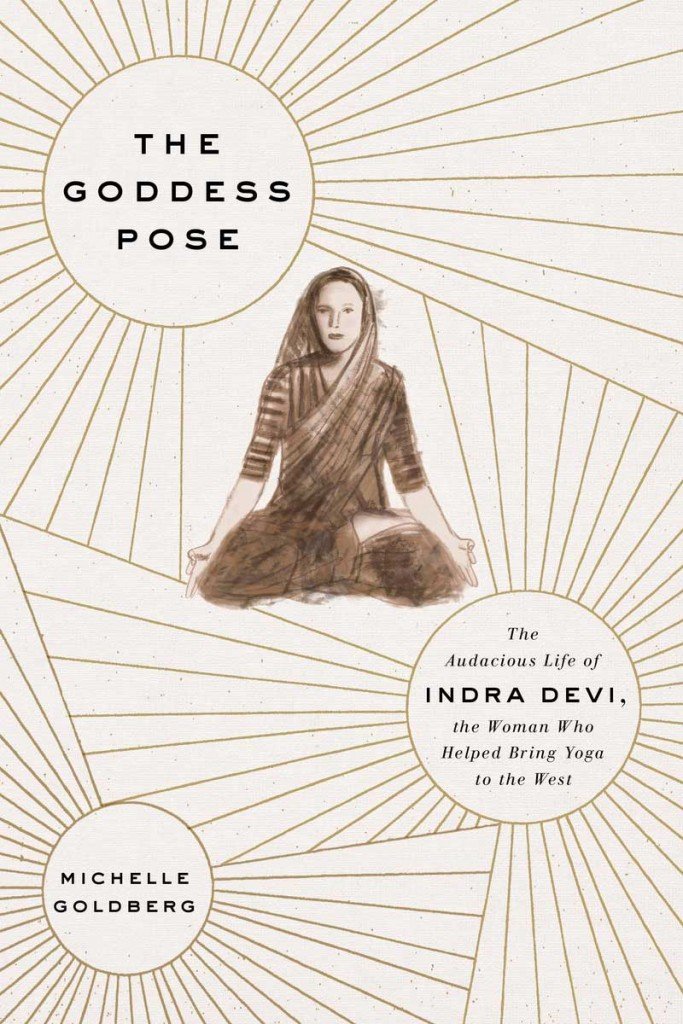

The Goddess Pose was released on June 9, 2015, by Knopf Publishing and is now available for purchase.

Comments (0)